Why do up-and-coming artists need theory?

After having taught at the Oslo National Academy of the Arts for eighteen years, art historian Åsmund Thorkildsen knows a good deal about the relationship between theory and practice.

“I’m not interested in playing up the differences between theory and practice,” Åsmund Thorkildsen says. “Rather, I want to move theory away from the purely abstract.”

The celebrated art historian and director of the Drammen Museum of Art and Cultural History will again be holding his lecture series on modern and contemporary art this autumn. The series is highly popular among students and a wider audience alike, and the places reserved for non-students have long since been taken.

In the following we will provide a taste of Thorkildsen’s lecture series both to those not lucky enough to have reserved a seat, as well as to those who will in fact be attending.

Education

As a lecturer, an intendant at Kunstnernes Hus from 1989 to 1999, and the director of Astrup Fearnley Museet until 2001, Thorkildsen has seen the peaks and troughs of the artist community’s relationship to theory, from the deep-seated interest of the 1990s to the current, more pragmatic approach.

Regardless of era, however, a key question will always be, Why is theory important to art students?

“The goal of my lectures is to make people interested in observing things deliberately and thoughtfully, and to help them acquire the skills to do so,” Thorkildsen notes. “The students, who are to dedicate their lives to their artistic practice, are given an introduction to the framework conditions that they will be working within. Ideally, my lectures provide them with tools they can use in their reflections.”

During some of the lectures, the participants read texts on art, written not by philosophers within the frame of their esoteric projects, but rather by artists and art critics. Thorkildsen is also big on illustrating his points with pictures.

“It seems obvious to me that when people see pictures, or objects and buildings for that matter, they also think about them. It is therefore essential to put the art in context, using concepts that help clarify their thoughts.”

Traditional divisions

Thorkildsen’s lecture series is organised under the auspices of the Art and Craft department. Is there any difference between teaching art theory at that department compared with at the Academy of Fine Art? Thorkildsen replies by looking at some of the predominant trends in the respective fields from a historical perspective.

“If we compare ceramics and painting, for example, we see that for the past hundred years or so the watchwords in ceramics have been tradition and stability. In painting, by contrast, there is an emphasis on surpassing the previous generation.”

When Thorkildsen looks at current practices, however, he detects a change in attitudes. At this year’s graduation exhibitions, it was perhaps harder than before to discern what had been produced at which department within the visual arts.

“Art is one of the few areas in society where you have the chance to be free, where you see a limitation but still do what you can to challenge this limitation,” he argues. “What is interesting for me is to observe the various artistic traditions on the basis of their opportunities and limitations, so as to be able to see what happens when they’re mixed together.”

The modern

The lecture series focuses on the historical development within various art movements, as well as on the upheavals that result from tensions between the visual arts and society at large. Thorkildsen concentrates on modernity in art, which by now has a 150-year history behind it.

The lectures are chronological. They begin in Paris in the mid-nineteenth century with the advent of the modern metropolis.

“This was an era of major social change. Artists had previously been commissioned by clergymen and nobility, but now they had to deal with an anonymous free market. This was the beginning of modern exhibitions, art collections and art criticism. The role of the artist became professionalised.”

The lectures then turn towards Vienna, with a focus on the Wiener Werkstätte, Gustav Klimt and other leading figures. The Viennese artists produced Gesamtkunstwerk, or total works of art, as designers, architects, ceramists, fashion designers and admen expressed a new view of life and regarded the various materials and traditions as a whole. Another important element is Bauhaus, which emerged from what had been an academy of art and craft.

“Bauhaus tried to maintain and incorporate the human desire for sensuous joy and beauty into the new design trends, which were to meet the requirements, needs and opportunities of the new society.”

The West in crisis

Around the time of the First and Second World Wars, both the liberal democracies of the West and totalitarian regimes such as the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany reverted to traditional pictorial representations.

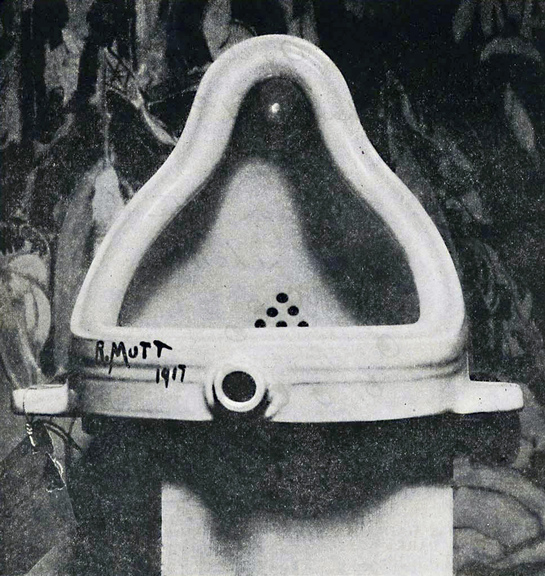

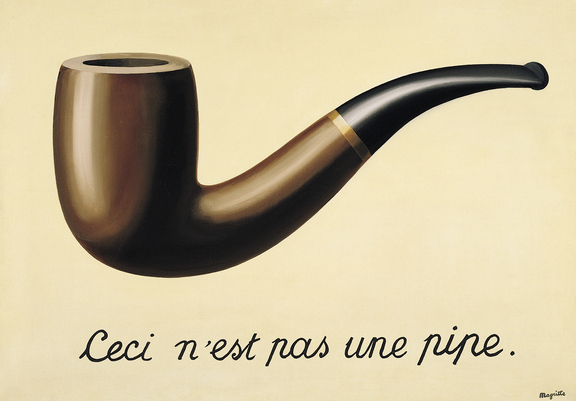

“This can perhaps be seen as a response to the chaotic dissolution of traditional values that took place during this era. This was also the age of Dada and surrealism, which were precisely attempts at peering into this chaos. In the series we immerse ourselves in psychoanalysis and the irrational and read texts about people’s dreams and urges as part of the social upheavals.”

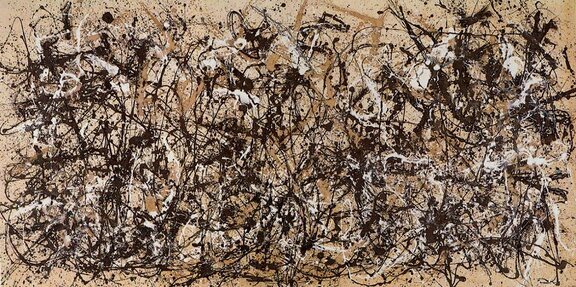

Modern art emigrated to America. This was an entirely physical process, in the guise of people fleeing from the Second World War. “What came to be known as the New York school then came into being and opened up for a radically new way of envisioning art,” Thorkildsen explains. “Whereas artists had previously shrunk the format of their works in order to translate the physical world into a pictorial world, they now situated their works within the same physical, sensory space that the viewers inhabited.”

The present and the future

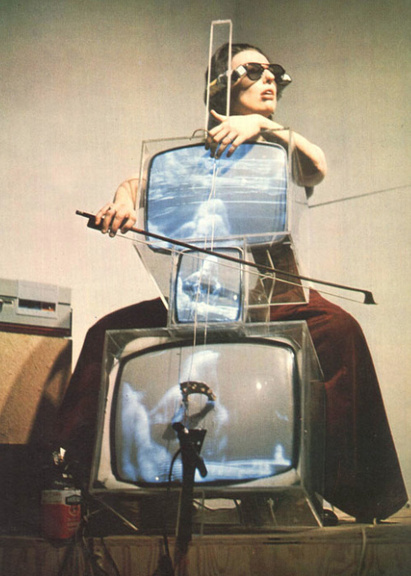

The lectures continue with minimalism, followed by a slight digression into the development of modern dance. This is followed by video and performance art as the continuation of seeing bodies, senses and objects as interactive entities.

“We end the series by reading about postmodernism – which mixes a variety of media and traditions – and the textual turn, appropriation and events and happenings.”

What, then, follows in the wake of postmodernism? Thorkildsen mentions digital art, before returning, surprisingly enough, to his home turf in order to illustrate how the future is also built on the past:

“Media reality is becoming ever more pervasive, both as the arena one culls images from and as a medium for dissemination and sharing. On the other hand, I don’t view this as just a matter of networks and digital dissemination. The Drammen Museum, for example, has some gorgeous folk art full of traditional rosemaling. We are used to looking at such rosemaling as being a uniquely Norwegian phenomenon, but in reality it consists of various hybrids that have been inspired by similar forms from all over the world. This is also a type of network, one that has existed long before the Internet was invented.”

Åsmund Thorkildsen, b. 1954

• Norwegian museum leader, curator and writer

• Director of the Drammen Museum since 2001

• He has previously worked as an intendant at Kunstnernes Hus 1988–99 and as the director of the Astrup Fearnley Museet 1999–2001.

• Read more about the lecture series

. It is no longer possible to register for the series this autumn, as it is full-booked.