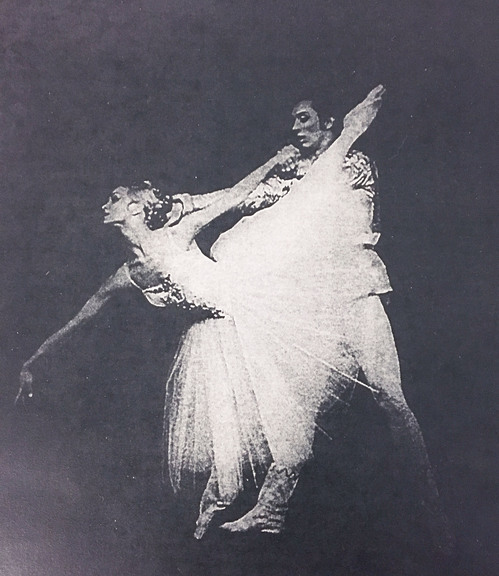

The master of the pas de deux

In 1983 he crossed the Iron Curtain from Hungary to dance with Norway’s most prestigious ballet company. Today, pas-de-deux teacher and trainer in classical dance, Lecturer Zoltan Szolnoki coaches aspiring ballet stars at the Oslo National Academy of the Arts.

Trudging down an Oslo street on a cold autumn day, the pavement wet with rain and slippery with fallen leaves, you might just pass Zoltan Szolnoki, who, with his glasses and greying beard, could easily be taken for a thoroughly ordinary man. At first glance you’re unlikely to notice anything that betrays his twenty-two years of background as a dancer of classical ballet at the highest level, or the fact that his route to Oslo’s most prestigious dance stage at the Norwegian National Opera & Ballet took him through the Iron Curtain.T

“There were several ways to get to the West from Hungary. You could defect, but then you could never go back. I chose to sign a contract that entitled the authorities in Hungary to ten percent of everything I earned. It was an option that allowed me to work in the West without killing the hope of seeing my family again,” he says.

New and challenging tasks

After twelve years dancing with the Hungarian National Ballet, he thus escaped the communist regime in Hungary, together with his wife and children, and ended up in Oslo. That was in 1983. For six years he had to send part of his income to the authorities in Hungary, before he was liberated by the fall of the Iron Curtain. And on stage in Oslo, he could devote himself to new challenges.

“There were many dancers at the Hungarian National Ballet and competition for parts was fierce. Coming to Oslo meant I could dance more exciting parts,” he says.

He danced for Norway’s top ballet company for ten years. Simultaneously, he assisted former ballet director Dinna Bjørn as a répétiteur and led classes for the company. For five years he worked as both a dancer and a ballet teacher. From 1991 to 1993, he returned to Hungary to study dance teaching at the Hungarian Dance Academy.

In 1994 he began as a part-time teacher at what was then the National College of Ballet and Dance. He also taught on the GDT programme (free daily classes for dance professionals, since assimilated into PRODA), and at other dance schools, before devoting himself full-time to the training of tomorrow’s top dancers at Norway’s foremost school for ballet, the Academy of Dance. The work at PRODA was a huge challenge that taught him a lot about teaching.

When girls jump like fish

“Are you going to be a star?” the pianist shouts across the room to Zoltan, on realising that someone is going to write about the 62-year-old.

“I am a star, but a falling one,” Zoltan answers with a laugh, but without any trace of arrogance.

The ballet stars of tomorrow laugh as well, while preparing on the floor in front of the mirror.

“Don’t let your arms turn to rain,” Szolnoki reminds his students. It might be grey outside, but in the studio the second-year students have smiles on their bodies as well as their faces.

Their dedicated teacher was trained in the Russian Vaganova method, a system that has produced some of the world’s most celebrated ballet dancers. Developed in St. Petersburg in the 1930s, the method aims in particular for harmony between arm and leg movements, and a more integrated functioning of the body as a whole.

“The number of boys in our classes at the Academy has been growing steadily. That’s good for everyone! It changes the dynamic within the class. The dancers motivate each other to reach higher when the gender mix is more equal.”

The Vaganova method finds its consummation in the pas de deux. In this dance between one man and one woman, all the premises of ballet come into play, and within the Vaganova system the final exam often consists of a pas de deux. Teaching the pas de deux is Zoltan’s area of responsibility.

“It’s a fun challenge, choosing pairs for the pas de deux; it’s pure psychology. There has to be a certain chemistry between the two who dance together. Obviously, height differences can be an obstacle, but anything’s possible. The most common mistake the girls make is to jump out of the hands of the boys, like a fish slipping from your grasp. They’re impatient and don’t wait for the boy. They don’t quite believe he’ll give them the support they need. The most common mistake among the boys, particularly those with a lot of strength, is to hold the girl at an angle on the floor. Of course, it shows off their strength, but there’s a danger of the girl injuring her toes,” says Zoltan Szolnoki.

His smile never fades for long when instructing the second-year class, which consists of three boys and four girls. The mood is bright in Studio 3 on the seventh floor of the former sail-making factory.

“Remember to breathe! You need air! Try not to squeeze your lungs too much. Without oxygen in your muscles, you’ll quickly get cramp,” he says, as the girls do complex jumps across the floor.

It is difficult to maintain lightness when the muscles are short of oxygen. The result should look effortless and expressive.

The youngest students at the Academy of Dance are just 15 years old.

“We can’t ignore the fact that to some extent we teachers become parent figures, or role models for them. I have two children of my own who are now in their forties, and I’m glad to be working with youngsters. I want them to feel safe, which is a precondition for the effort needed to push ahead and become better as dancers. I must guide my students to find their own forms of disciplined working,” says Szolnoki.

Pas de deux assistant at the Opera

Zoltan Szolnoki was pas de deux assistant to former ballet director Dinna Bjørn, and helped to professionalise training for young dancers in Norway; suddenly they started winning competitions and securing international engagements.

“I enjoy teaching, and it’s especially challenging when I have mixed-level classes. Here at the Academy, the jazz and modern dancers also have a classical ballet component. My teaching method is that no matter what happens in the ballet studio, it’s something the students can learn from. The mistakes students make should be treated objectively and used as material for reflection and further development. Learning to dance involves both physical and intellectual work. That means you have to work physically and think at the same time. For that to happen, the relationship between teacher and student has to be one of cooperation,” he explains.

He describes an environment that is open and constructive.

“It’s by no means common to find conditions like the ones we have here, where bringing out the best in students is a shared endeavour. In many ballet schools, teachers tend to talk about ‘their students’ and they compete among themselves rather than help each other. I’m proud that we can show the world the way we develop good students here, by providing constructive criticism and a positive, open environment, and the way students progress under the motto ‘freedom with responsibility’. We want students to graduate from the Academy with a good feeling,” he says.

Academy Profiles is a series in which, each month, the editors of khio.no present one of the specialist staff members at the Oslo National Academy of the Arts. The presentation will usually take the form of an interview, and will appear in Norwegian and English. The aim of the series is to paint a fuller picture of activities at the institution and to promote international contacts and interest in our academic and artistic research.