Academy Profile Hans Hamid Rasmussen: Filling the Holes with Meaning

Hans Hamid Rasmussen is professor of art and subject area coordinator for textile art at the Art and Craft department. For Rasmussen, embroidery has become a technique for translating intercultural experiences from growing up in Algeria, Hungary and then finally Norway. Embroidery is a practice where Marx meets God.

Rasmussen was born in Algeria, but he, his sister and his Norwegian mother have all lived in Norway since the early 1970s. His early life was full of drama. “Because of the coup d’état in Algeria in 1965 and my father’s political role under the leadership of Ben Bella, my family and I found ourselves right in the middle of the violence,” he recalls. “At night, soldiers broke into our flat and threatened to harm those of us who were children in order to force my mother to provide information. Father was thrown in jail and tortured. Later on we were allowed to visit father, and things like illegal newspapers were smuggled in my nappies.”

“Father was released after a while and given the choice of either switching his political allegiance or leaving the country. He chose to leave, and mother became isolated from her social network and placed in house arrest. Thanks to Norwegian benefactors and Amnesty International, mother received an art grant from UKS [Unge Kunstneres Samfund] and was able to bribe the authorities so that we were able to buy a passport for me and my sister. That’s how we were reunited as a family in Budapest. A year later mother decided to take the kids and move back to Norway. That was in 1971, and after a few, short summer weeks, I began at this white-painted school in Østbygda in inner Østfold. Our family past of having parents who were deeply involved in international politics – with people like Che Guevara, Pierre Bourdieu and Frantz Fanon among the people they knew – that all faded away. In 1971 there were few people with names like Malika and Hamid in Østfold. Even though mother was Norwegian, our presence represented a Norway that was changing.”

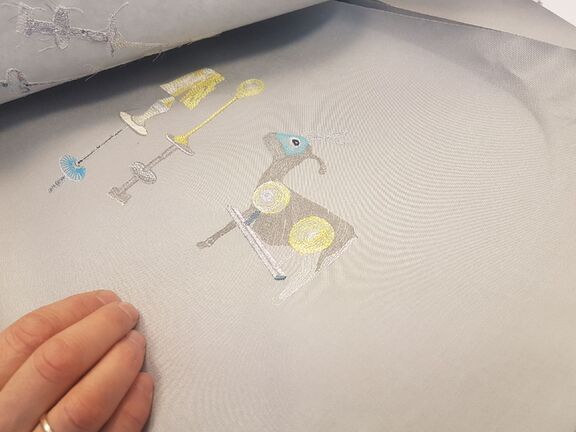

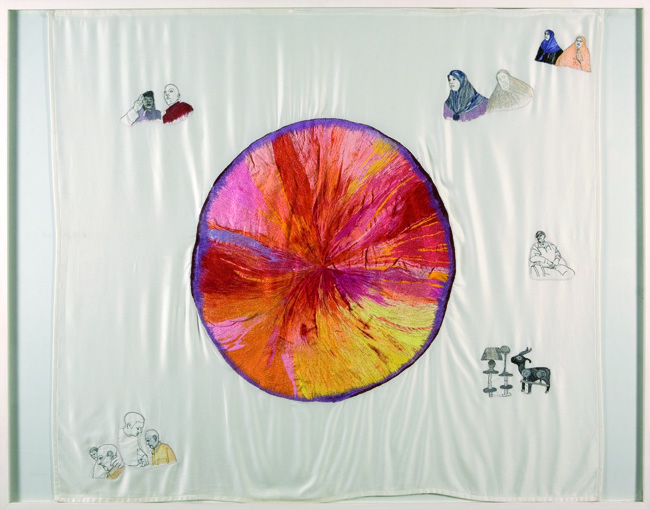

Hans Hamid Rasmussen was seven years old when he moved to Norway. His first language was French, but it wasted away from disuse during his first year in Norway. In his works, which are photographs that have laser cut and then enhanced with digitally programmed embroideries, he explores intercultural dilemmas and the possibility of expressing both the silent, introverted language he knew from Algeria and the extroverted language he knows from his formative years in Norway.

The end of Western hegemony

Hans Hamid Rasmussen is currently serving his second term as the subject area coordinator for textile art at the Academy, where he has worked for ten years. Not many artists were working with fabric when he himself was a student in the 1990s, a watershed era for the Academy of Fine Art and its outlook on art.

“I studied at the Academy of Photography at Konstfack in Stockholm, and at the Academy of Fine Art in Oslo. My studies at Konstfack and the AFA in the 1980s and 1990s really changed my understanding of art. It was not only that we were introduced to new techniques, but even more important for me was that we almost overnight got to know philosophy, linguistic theory and art history in an almost entirely incomprehensible mix. Throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s, the consequences of the political and economic changes taking place all over the world would show that the Western hegemony in the world of art was over. Something that was new for us was that artists who lived in countries and regions that hadn’t previously been represented in the art scene were now being allowed to participate, such as for example at documenta X in 1997 and its follow-up Documenta11 in 2002.”

“I studied at the Academy of Photography at Konstfack in Stockholm, and at the Academy of Fine Art in Oslo. My studies at Konstfack and the AFA in the 1980s and 1990s really changed my understanding of art. It was not only that we were introduced to new techniques, but even more important for me was that we almost overnight got to know philosophy, linguistic theory and art history in an almost entirely incomprehensible mix. Throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s, the consequences of the political and economic changes taking place all over the world would show that the Western hegemony in the world of art was over. Something that was new for us was that artists who lived in countries and regions that hadn’t previously been represented in the art scene were now being allowed to participate, such as for example at documenta X in 1997 and its follow-up Documenta11 in 2002.”

Rasmussen believes that students who study textile art at KHiO today will be highly sought after.

“Materialbased art experience a renewed interest, partly because asian artists has received attention the last decades. Many more people collect art now, especially from China and India, and material- and craft-based works are in a much stronger position there. They represent the market forces, as a result, Europe as well is trending towards craft-based works. I don’t think the interest in materialbased art is a passing fad. Demand is on the rise, and our students will be attractive because there are not that many who are practised in the techniques that the students learn at the Academy.”

Rasmussen himself found out soon after completing his studies that embroidery responded to his need for expressing the many issues and challenges he encountered from having an intercultural background.

“At the beginning, I literally knew nothing about embroidery. I got hold of a folk costume embroidering kit and soon developed a pedantic kind of embroidery based on knowledge about drawing with hues and nuances I had acquired from drawing classes at Konstfack in Stockholm and the Academy of Fine Art in Oslo. Learning new forms of self-expression can be compared with discovering a new language. With the help of many positive and well-willing people, I have acquired some knowledge of the field, which along with an enduring interest in human relationships constantly leads to new visual works.”

“At the beginning, I literally knew nothing about embroidery. I got hold of a folk costume embroidering kit and soon developed a pedantic kind of embroidery based on knowledge about drawing with hues and nuances I had acquired from drawing classes at Konstfack in Stockholm and the Academy of Fine Art in Oslo. Learning new forms of self-expression can be compared with discovering a new language. With the help of many positive and well-willing people, I have acquired some knowledge of the field, which along with an enduring interest in human relationships constantly leads to new visual works.”

Back to Algeria

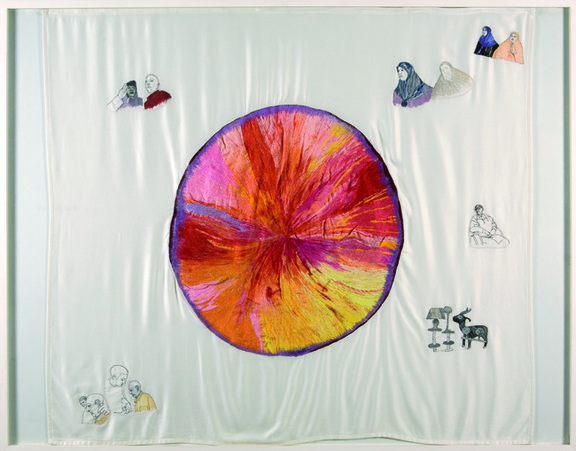

In 1993 Hans Hamid Rasmussen was invited to Suomenlinna in Helsinki to hold his first solo exhibition, titled Fremmen.

“During the process I explored the concept of being foreign in different contexts. I ended up making portraits of twenty-two children with various physical deformities on two bedsheet-like linen textiles. The works were discovered by various curators who helped me out into the world. Support from the Office for Contemporary Art allowed me to travel to Algiers, my city of birth, with a camera stowed away in a football bag. With help from Thomas Saenger, a colleague of mine who really knows what he’s doing, the material was edited into a video work that was presented at KIASMA in Helsinki in 2001.”

The video material subsequently served as the subject matter for textile works, specifically digital embroideries. Technological developments have enabled Rasmussen to cultivate and reproduce a universe of images on the basis of his experiences from manual embroidery.

The video material subsequently served as the subject matter for textile works, specifically digital embroideries. Technological developments have enabled Rasmussen to cultivate and reproduce a universe of images on the basis of his experiences from manual embroidery.

“During my first trip to Algeria and the capital Algiers, I was taken care of by my mother’s old friends. My visit was an encounter where I stood on the outside and had little opportunity to understand my social surroundings. I managed to find the house we lived in before we fled the country, and it was naturally enough a powerful experience, even as it was hard to relate to it all. With the help of my friends we tried to go into the kasbah, which is the Old Town in Algiers, but we chose to turn around when they warned me about the dangers we were exposing ourselves to there.

“During my second trip, which I took with my father and my half-brother Karim, we visited relatives who live in the kasbah. It may be difficult to understand the differences we call cultural identity. Even so, I feel that different social encounters usually build on a sense of recognition, in other words that we identify feelings and expressions in the other person. Over time, more complex social behaviour comes to the surface, including certain expectations that may be difficult to understand or accept. In Algeria, your various familial bonds are seen as the social space that you as an individual are associated with. That’s something I particularly noticed during my first visit in 2000, when a guest asked me about my Algerian family’s name, whereupon the host interrupted the other guest, saying that there I was the son of their house, in other words that my father’s family was not a topic of conversation. I interpret this is as meaning that relationships are developed along the family’s lines and extensions. As a Norwegian I relate to an ever-present public space where I as a citizen know my place, my rights and my duties. In my mind, this space is elevated above virtually any personal relationship.”

Reconciliation and loss

When Hans Hamid Rasmussen visited Algiers with his father, the two of them managed to visit the apartment where they had been put in house arrest before his father was exiled and the rest of the family fled the country.

“The man who opened the door was the same person who had once informed on my father to the new regime. But standing there in the doorway, father met an old comrade and warrior he shared a past with. There was no sign of any rancour. It was as though they were trying to reconcile. The experience made me think of my own personal process with my father. In the flat, all of mother’s Norwegian books and items looked as though they hadn’t been moved for all these years. My grandfather’s old Kabyle cupboard still hanged in the same place in the hallway on the way to the bedroom that I had once shared with my sister. All the items had been dusted, as though the items in the flat were part of a public history that was respected by everyone who had lived there. These were items that they didn’t look on as their own belongings, but nor did they belong to my mother and father.”

“I have often thought of Aksel Sandemose’s novel A Fugitive Crosses His Tracks after that visit. When we left the flat, something had let go of me. The life we had led in Algeria was, at least outwardly, largely based on my father’s life and role in the public sphere. He was a young Marxist and lived through major upheavals in the society he was part of. The way he broke with his own family in Algeria must have been just as radical as the break he made during the period my mother met my father – perhaps it was even more radical. Along with other young Algerians, they were to form a new state free from French colonial oppression. The colonialists had left behind a traumatised and divided populace, sky-high illiteracy and ruined infrastructure – on the whole, large parts of the county were in tatters. I have missed and continue to miss understanding what he represented in my life, and it has taken time to get over the feeling of betrayal when he, as a father, left us.”

Growing up with Marx, Lenin and God

Hans Hamid Rasmussen says that when they moved to Rakkestad in inner Østfold, they encountered a local community that was highly Christian. At school they sang grace together every day.

“‘Oh, you who feed the little bird, bless our food, oh Lord, amen!’ As a French-speaking kid who had just moved to inner Østfold, I misunderstood the local dialect there and thought they were saying “Oh, you who are called Little Bird”. That made it possible on a certain level to reconcile Marx, Lenin and God. This form of metaphysical crisis has basically shaped my thinking as a person, including my interest in art.”

“It was in Østfold I felt as though at one with the forest. This connection to the forest acquired a new dimension later on when I learned about the metaphysical Germanic relations between humans and the forest, as recounted to me by a woodsman while I was working as a raftsman along the river Glomma. But my years as an active member of Nature and Youth were also formative, as that is where we learned about combining political theory with respect and love for endangered species and environments. As a youth in Rakkestad I also encountered the first sign of structural prejudices expressed by populists. This included the school dentist in Rakkestad, Øystein Hedstrøm, who was a member of Parliament for the Progress Party and who is known to have made ever more extreme xenophobic statements.”

An architectural and social patchwork

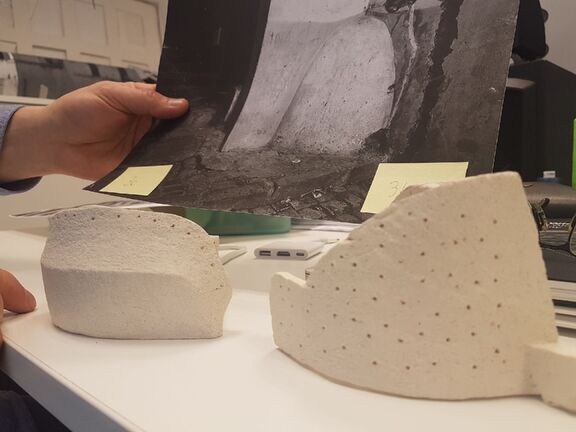

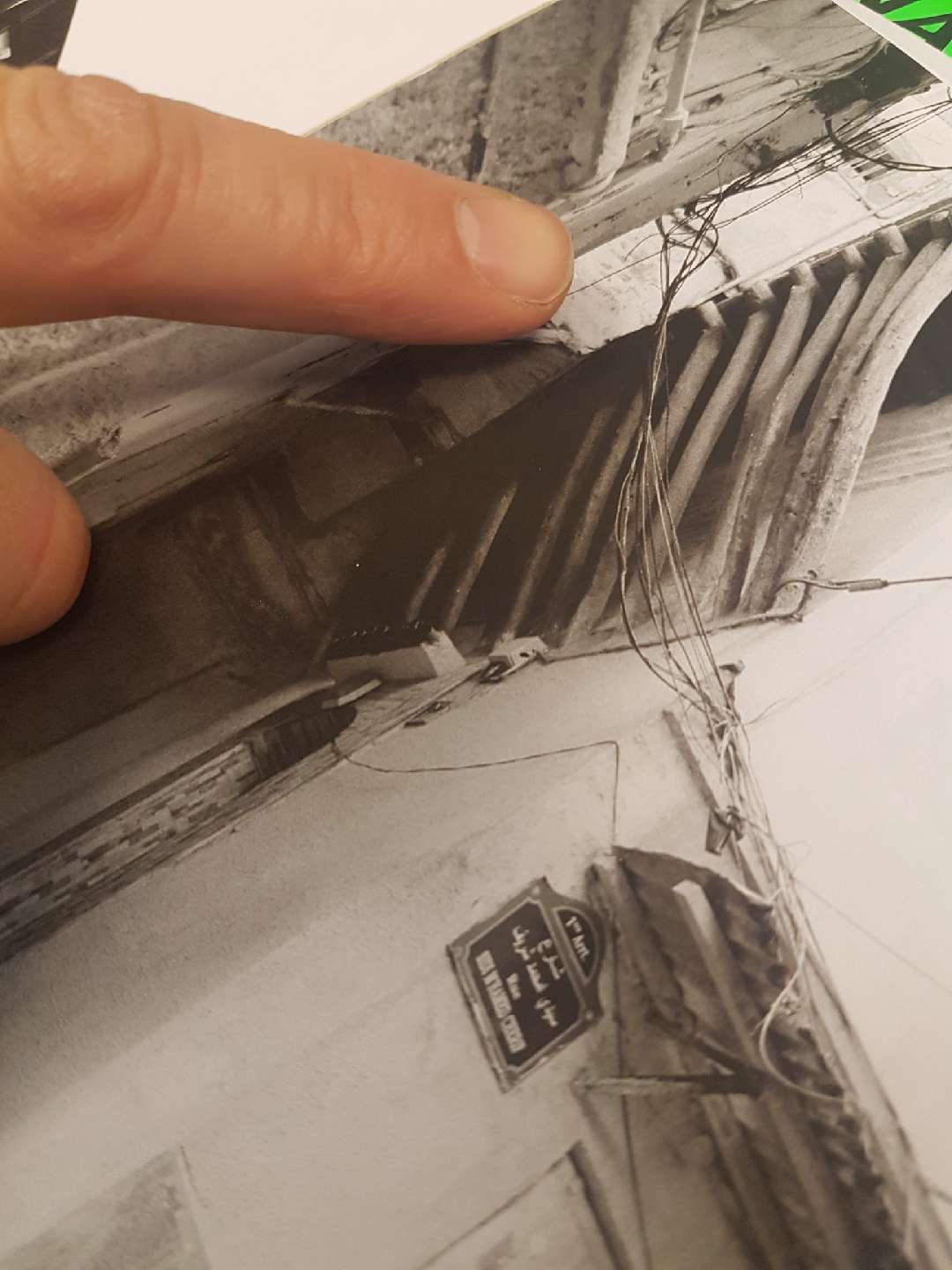

During 2016 Rasmussen received a KUF grant for artistic research and travelled back to Algeria. With him he took his analogue 4 x 5-inch camera, which captures pictures on plates.

“At three in the morning I went into the kasbah to take pictures. I wanted to develop works based on the distinctive urban structure there. The city itself has been built over the course of centuries. It shows traces from different eras. Some of these traces are clearly visible, but usually the buildings are hidden since they have been built right by one another with the room’s opening turned inwards. Over time, various events  have shaken and transformed the city. Entire buildings and walls have caved because of earthquakes, the bombing from the colonial war is still visible, buildings have collapsed, and remaining walls that had perhaps previously been the interior of the house with doors and stairs have been walled in. The kasbah changes and gets fixed up, and buildings either grow together or become partitioned, depending on people getting married or falling out. There are several layers of tunnels under the neighbourhood, but also at the street level you can notice underpasses that stem from houses merging above head level. The spaces in between are still large enough for donkeys and people to pass through.”

have shaken and transformed the city. Entire buildings and walls have caved because of earthquakes, the bombing from the colonial war is still visible, buildings have collapsed, and remaining walls that had perhaps previously been the interior of the house with doors and stairs have been walled in. The kasbah changes and gets fixed up, and buildings either grow together or become partitioned, depending on people getting married or falling out. There are several layers of tunnels under the neighbourhood, but also at the street level you can notice underpasses that stem from houses merging above head level. The spaces in between are still large enough for donkeys and people to pass through.”

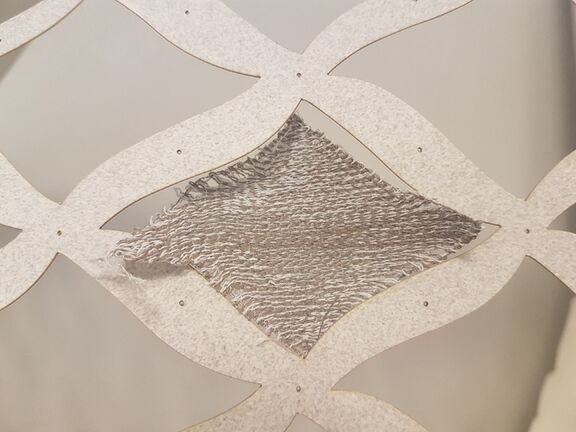

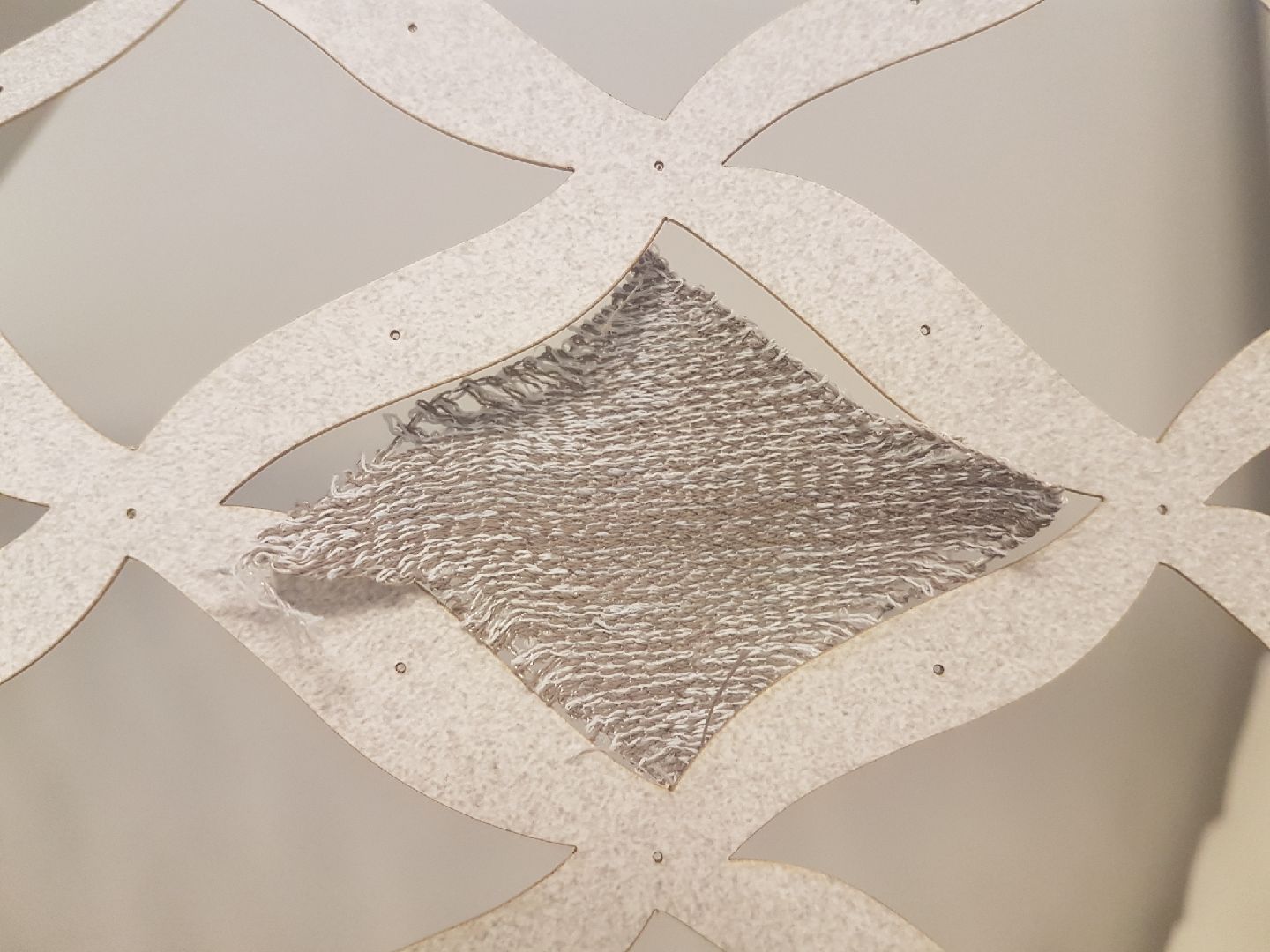

When Rasmussen returned home to Oslo, he worked on digital embroidery and laser cutting. He had found a gelatine-based substance that can be removed with warm water and that makes it possible to develop layers upon layers of variously coloured seams or to develop textile objects. Using new types of thread with ceramically enhanced matte finish surfaces that harmonise with the photographic surface, it is possible to sew different textiles that can be joined in a photograph.

“The textile surfaces add a physical disruption to the photograph that corresponds to what I want to express. The houses in the kasbah often use more or less textile principles to resist the destructive forces that are caused by the frequent earthquakes. In my quest I have been particularly interested in the encounter between the various angles and disruptions between the buildings. Various destructive forces, as well as the way people build and tear things down, give rise to narratives between the houses that interest me. A door has been walled in – is it related to a window on the other side? The corner with the small hatches on the wall – what are they, and are they related to something else I can’t see? I have built a few houses myself, and when I see a wall without straight lines, I look for logical connections.”

Contexts and fragments of architecture

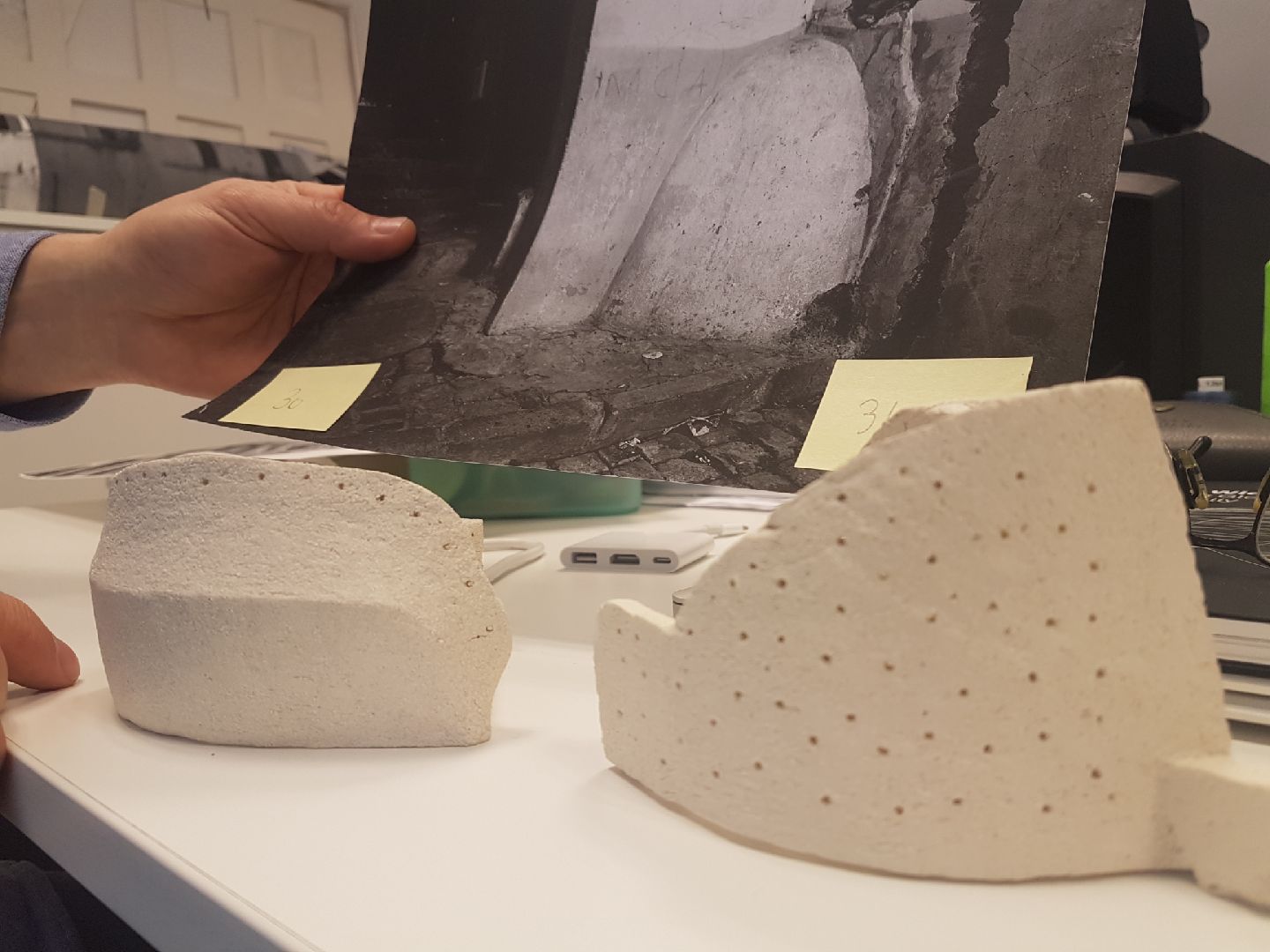

In a new project he has recently begun, Hans Hamid Rasmussen will explore the encounter between cast bronze and fabrics. The plan is to create models based on the photos he took in the kasbah.

“For many years now I have been fascinated by Kurt Schwitters’ Merzbau project. Schwitters’ was one of the true ground-breaking artists of the twentieth century and explored an array of genres such as collage, sound poetry, architecture, sculpture, assemblage, painting and typography. In 1919 he developed his own artistic movement known as Merz. He used the items he found, such as planks, rocks, chains, plaster and cardboard. He even used human hair and urine in his structures, and he often incorporated the various elements either partially or entirely into the structure. Schwitters’ himself said that ‘Merz makes connections, ideally between everything in this world’. Using hidden rooms as part of the experience of a work of art challenges the viewer’s opportunity to form an opinion on the basis of the available visual information. Schwitters’ collages show a fragmented life that amongst other things involved fleeing from the Nazi regime, but they also show a person who is constantly searching to find connections in this world.”

“For many years now I have been fascinated by Kurt Schwitters’ Merzbau project. Schwitters’ was one of the true ground-breaking artists of the twentieth century and explored an array of genres such as collage, sound poetry, architecture, sculpture, assemblage, painting and typography. In 1919 he developed his own artistic movement known as Merz. He used the items he found, such as planks, rocks, chains, plaster and cardboard. He even used human hair and urine in his structures, and he often incorporated the various elements either partially or entirely into the structure. Schwitters’ himself said that ‘Merz makes connections, ideally between everything in this world’. Using hidden rooms as part of the experience of a work of art challenges the viewer’s opportunity to form an opinion on the basis of the available visual information. Schwitters’ collages show a fragmented life that amongst other things involved fleeing from the Nazi regime, but they also show a person who is constantly searching to find connections in this world.”

Rasmussen is also preoccupied with the theories of the French writer and philosopher Jacques Derrida, who was born in Algeria. He is one of the leading figures within poststructuralism and postmodern philosophy.

“In several layers in my life, my work leads me to ideas about language that I have found in Jacques Derrida – the importance of repetitions and differences, but also about remembering a private sequence of events, which is something other than what we remember together. I have had to be open to sequences of events in different ways. I have to constantly come to terms with myself with the different private and public spheres that arise between different cultures. I think it is exciting to search for the beautiful and the practical. In that search, I recognise my own childhood years and the need to fill what I don’t understand with meaning.”

Hans Hamid Rasmussen (f. 1963 i Algerie) bor og jobber i Oslo. Rasmussen studerte på fotoakademiet ved Konstfack i Stockholm og på Statens kunstakademi i Oslo. Rasmussen var stipendiat ved Kunstakademiet i Trondheim med midler fra Program for kunstnerisk utviklingsarbeid med prosjektet Homage to a Hybrid, under veiledning av kunstneren Nina Roos, filosofen og kuratoren Sarat Maharaj og kuratoren Maaretta Jaukkuri. Han er professor i kunst og fagområdeansvarlig for tekstilkunst på Kunst- og håndverksavdelingen ved Kunsthøgskolen i Oslo. Rasmussen la nylig frem det kunstneriske utviklingsprosjektet Walking the Kasbah på Østfold kunstsenter (2017), og prosjektet har også blitt vist som en separatutstilling på Martin Asbæk Gallery i København (2018). Rasmussen har også deltatt på utstillinger som den 26. São Paulo-biennalen (2004), den 3. Guangzhou-triennalen (2008), Göteborgs Internationella Konstbiennal (2011) og Hangzhou-triennalen for fiberkunst (2016).