Do androids dream of electric sheep?

Trine Wester is an artist and the director of one of KHiO’s most high-tech workshops, dForm. She is fascinated by the interface between technology and philosophy, technology and art. How does technology shape who we are, and what kind of opportunities does it open up for artists?

What happens when we create objects, but without using our hands?

This is a question that preoccupies Trine Wester. In a tradition that treats the contact between the artist and the object she creates as a self-evident aspect of aesthetics, digitally produced art is bound to challenge a few preconceptions.

Trine Wester trained as an artist at Oslo National Academy of the Arts. In her work she mixes photography, animation, digitally generated images and three-dimensional objects. Her interest in the philosophy of technology forms the starting point for both her own artistic work and her teaching at the Academy. After labouring for several years to establish a digital production workshop at the school, that dream has now been realised. She came up with the idea on seeing a 3D printer at what was then the Oslo School of Architecture. A machine that could print out physical objects based on digital models. A machine that allows you to create objects without using your hands. What kind of art objects could one conceive with a device like that?

“Back then, 3D-printed objects seemed like a sign of change and new opportunities. The technology involved was a tool for new ways of thinking,” says Professor Trine Wester at KHiO’s Art and Craft department today, many years after she saw her first 3D printer in action.

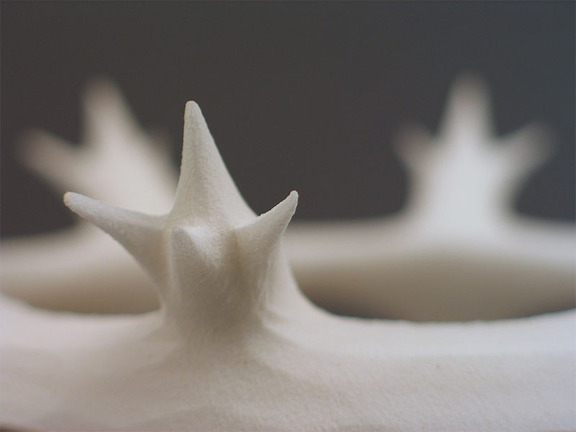

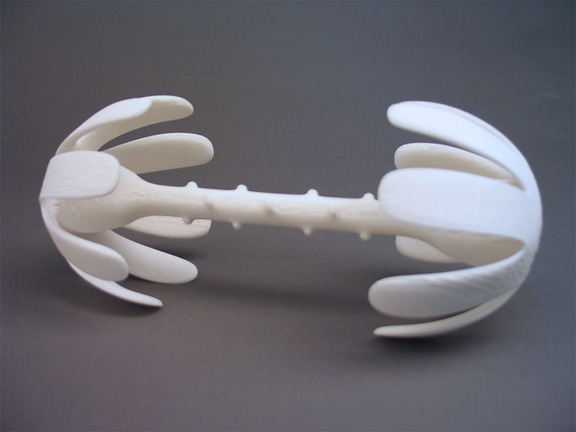

“Digital technology allows us to create objects with a kind of complexity we could never achieve when making things by hand. It becomes physically possible to model and produce a ball within a ball within a ball within a ball, ad infinitum. You can scan a piece of wood and record its structure. You can manipulate data and generate shapes that you could never visualise using any other method. But with computer-aided design you also lose something. Digital information consists of ones and zeroes, either/or. That rules out certain possibilities and nuances. And it’s precisely this I want students to be aware of: what they lose and what they gain when using digital technology,” says Wester.

Printing porcelain

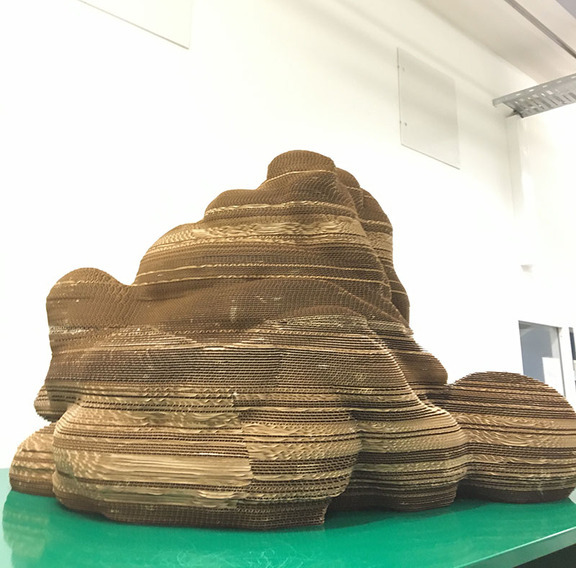

At dForm they have the equipment for 3D scanning and 3D printing in a wide range of materials and to a range of different end qualities. There is also a laser cutter that can cut and engrave a variety of materials, and facilities for photogrammetric scanning and the use of Kinect sensors.

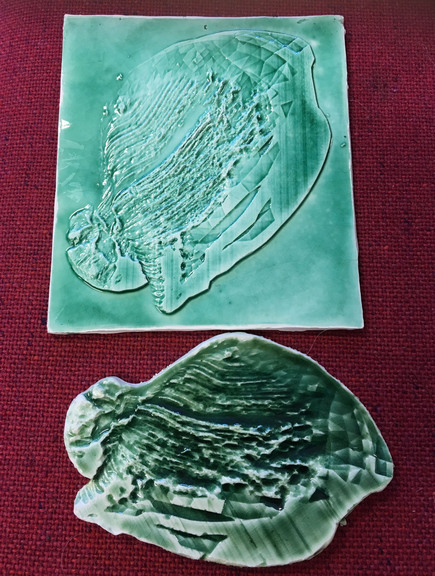

Together with students, Wester has experimented with the 3D printing of various materials, including porcelain from porcelain powder. Once an object has been printed, it can in principle be glazed and fired.

“New technology can also give new life to old techniques, such as the lithophane, which involves engraving porcelain to different depths so as to create an image that is seen when bright light passes through the translucent material. Whereas this was traditionally done by hand, the same thing can now be done with extreme precision using a laser cutter,” she explains. To illustrate, she holds a laser-cut piece of porcelain up to the window in the dForm workshop. As the sunlight falls on it, it reveals a famous painting by Hertevig.

New possibilities

“I’m interested both in exploring the new possibilities technology offers, and in speculating on how new technologies are changing the ways we view ourselves as human beings. When we start using new technology, it changes our behaviour,” she says.

For the project “The Techno Sublime”, Wester received funds from the Norwegian Artistic Research Programme (NARP).

“By setting the discussion about technology within a humanistic tradition, I want to focus on what strikes me as our principal contemporary narrative: the one about technology. I want to raise awareness of and interest in the philosophy of technology among students at the Academy, and to get them involved in exploring how it can be used in individual artistic practices,” Wester says.

In conjunction with this NARP-backed project, Wester initiated a seminar on Heidegger and technology, helped to organise the seminar “Agenda: Our Digital Selves”, and arranged a course for the so-called corridor weeks on the theme of the techno sublime.

Passionate communicator

This autumn, at Moss Kunstforening, Wester will exhibit objects consisting of 3D collages that were subsequently 3D scanned and manipulated with simulation software. Thus they are transformed into virtual objects in a state of dissolution or melt-down; the melt-down is achieved using software triggered by a few taps on the computer keyboard. The resulting artworks are visualisations of this process, in the form of either still images or animations. The works add up to a study of materiality – in virtual space, as physical material, and in the space between the two.

A passionate communicator, Wester has fought both for greater acceptance of the use of new technologies in artistic practice and for students to have access to these technologies.

“I want to teach students to use an array of methods and approaches. As an artist, there are so many ways of relating to technology. Everything from seeing computers as useful tools for the production of art, through to viewing technology as a flexible medium for experimentation, or taking the philosophy of technology as a context for one’s own work. As a teacher I have a responsibility towards a part of our heritage, the period before technology gained such a dominant place in our lives – not that things were necessarily better in the past. I’d be the last to suggest they were. But that’s something students all too often take for granted,” she says.

“Our lives are ruled by technology. So many things just wouldn’t happen if the technological systems we live with every day were switched off. Would we be able to shop, pay our bills, contact each other, wake up in the morning?” Wester talks about drones and the surveillance society, about the Quantified Self Movement, which uses pedometers and other measuring devices on our smart phones to manage every aspect of our lives.

“Is this the world we want, and is there an alternative? What will the consequences be for us? As an artist one can throw light on such questions without having to declare oneself as either pro or contra. And a hands-on involvement with new technologies is a good foundation and starting point if you want to say something meaningful about these developments.”

Links:

Internet

Trine Wester's homepage

Academy Profiles is a series in which, each month, the editors of khio.no present one of the specialist staff members at the Oslo National Academy of the Arts. The presentation will usually take the form of an interview, and will appear in Norwegian and English. The aim of the series is to paint a fuller picture of activities at the institution and to promote international contacts and interest in our academic and artistic research.