Playing around in all seriousness

It’s a Wednesday morning in September and 18 students from the teacher training programme (PPU) are being visited by nine five-year-olds from the nearby Seilduken Day Care Centre. But when the little imps crouch down to become tiny nuts that then grow into big trees, they are not only playing but also helping educational principles be put into effect.

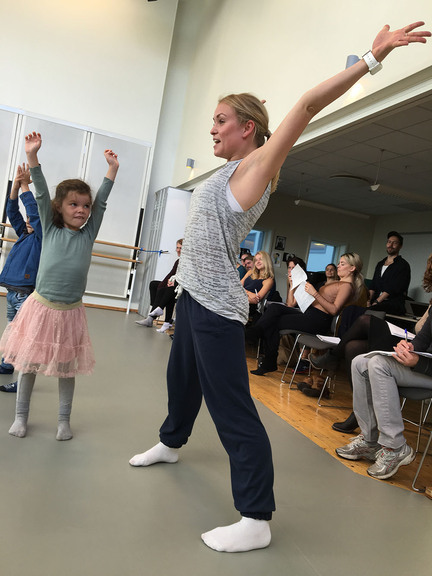

For an hour or so in Studio 8 on the sixth floor of the Academy building, the five-year-olds help the PPU students become even better educators, although they themselves are joyfully unware of this fact as they run screaming over a “deadly snake” consisting of a blue scarf. While four of the PPU students give the children tasks that most of all seem like play, the remaining 14 students and their teacher Marianne Schwarz, with pens raised and notebooks on their laps, study how the children play and how the students manage the session.

It’s not exactly a natural situation for playing and learning, but the five-year-olds have been here several times before and are beginning to get used to being observed.

“The very best and very worst part of working with such small children is their spontaneity,” says Gerard Garro, who has a background in theatre.

Actors and dancers

All the PPU students have a background in dance or theatre, and they learn to use their educational skills during the programme. The programme is rooted in both theory and practice, and the nine children have been invited to participate in the play-based session so as to allow the students to put a few educational principles into practice.

“In this part of the programme, the students learn about dance and theatrical play, with the aim of making the children aware of body and space,” explains Marianne Schwarz, the dance and theatrical play teacher. “The children also learn about power, tempo and using their body to express emotion. The students set up exercises for the children based on the theories they have learned in class.”

When the children run around the room or play their way through it, they unwittingly learn how to understand space. And when they stretch up from the acorn position, they learn to control their body.

As Schwarz explains, “The point is for the children to experience and learn concepts such as being down low and up high, above and below, large and small. What appears to be playtime in this room has been organised according to a clear system, and the students must state the desired goal for each exercise.”

The Academy’s practice-oriented teacher training programme (PPU) is a one-year programme for dancers, choreographers and actors who want to work as teachers and educators in the field. The programme qualifies the students to work as teachers in primary schools, secondary schools, folk high schools and adult education, as well as in culture schools and private schools where dance or theatre is taught. Applicants with other backgrounds from the field of dance are also eligible to apply. The programme includes 12–14 weeks of integrated and supervised practical training.

Creating things with children is fun

“It’s fun to get such immediate feedback on whether something is working or not,” says Vilde Halle Ekeland, whose tasks this particular Wednesday morning include the children’s acorn-to-tree exercise.

In addition to being a dancer, Halle Ekeland is currently studying to become an educator. “To work in education is to work with the unexpected,” she says. “You don’t know what’s going to happen the next day. I quite like to work with people, and as in this case with the day care centre, the group dynamics are constantly changing.”

“For me, it is important to become more confident in myself and in my role as an educator,” says Gerard Garro, who spent part of the session talking about the body and the names of all the fingers. “I have a fair amount of classroom experience, but the theories I’m learning here provide me with an entirely different foundation for teaching.”

Rooting educational work in solid theory

The PPU students learn to work on play, creativity and making things with children, as well as on collaboration, improvisation and composition. The practical training allows the students to experience the various aspects of the teaching profession and to learn hands-on how to plan, organise, carry out and evaluate their teaching by using principles from educational science. The training is carried out with pupils from various age groups, and later on the students will engage in practical training at a culture school and, for a more extended period of time, at an upper secondary school and its music, dance and drama programme. The students will also receive a comprehensive theoretical instruction.

“Now I know more about how I want to be as a teacher, and I’ll be able to justify my decisions by referring to theoretical principles,” says Geir Baldersheim Leirvåg, whose background is in dance. The task he had assigned the five-year-olds was to jump over a blue scarf re-imagined as a deadly snake. The children had to jump both over and under the scarf, acquiring a sense of spatial understanding by moving about through the room.

Baldersheim Leirvåg’s task was followed by Tuva Hennum’s much more language-based tasks, where the five-year-olds were to recite an onomatopoetic poem. The children began by warming up their mouths by pretending to eat chocolate. Some of the boys mischievously shouted out “Yuck!”, while the others obediently checked to see whether any morsels of chocolate were left in their mouth.

“I think I have become clearer and more confident in my role as a teacher,” Hennum notes. “And maybe it will also help me in other areas of life. Perhaps it will even help me in my work as a director, because what motivates me is my love of my chosen field, the creative world of the theatre.”